The area we now call Germany was a bit of a cluster fuck in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Made up of hundreds of small independent states and fiefdoms once tied together under the auspices of the Holy Roman Empire, a series of religious schisms and persecutions, devastating wars, and invasions by the French and others had left many common people impoverished and eager to find a new beginning in a place where things weren’t nearly as shitty. It was into this mess that William Penn waded in 1682, eager to try and convince whomever he could to immigrate across the Atlantic to his new colony of Pennsylvania whose motto was ‘we don’t give a shit who you are’. Though not overly successful, aside from some Mennonites who were tired of being treated like crap for having a slightly different belief about proper Christian worship, it did at least create an idea amongst many Germans of a possible better life across the sea. Over the next several decades handfuls of other Germans followed, selling themselves into indentured servitude to make the journey.

The first mass migration of Germans to North America occurred in 1709. A combination of famine and French invasion in the Palatine region of Germany had led to a refugee crisis, with over ten thousand Germans taking refuge in Britain. Much like today, this sparked a lot of debate, with some claiming the Germans would be beneficial for the economy and others claiming they were a bunch of poor disease ridden mooches who should go back to where they came from. The British government solved this little issue by shipping the Germans to other places, including some 3,000 which got shipped to New York where they were forced to do labor on public works projects to pay for their passage. After the debt was paid, the Germans were given lands in the interior to settle, near territory claimed by the Iroquois Confederacy, who weren’t really known to be the welcoming sort. However, luckily for the Germans, the Iroquois viewed them as more of an opportunity then a threat. At the time, the Iroquois leaders were beginning to recognize that the world was quickly changing, and if they wanted a place in it, they’d have to change too. The Germans were given access to land and in return they taught the Iroquois about European agricultural practices, a relationship which benefited both sides greatly.

The success of the German colonies in New York convinced more Germans from Palatine that heading off to America was in their best interest. Some were refugees who had to enter indentured servitude to make the passage or members of persecuted religious minorities like the Amish and the Mennonites, but many were farmers attracted by promises of free land. A farmer who owned just an acre of land in Germany, could own over 100 acres of land in America. A good portion of the German immigrants were literate and educated. They travelled down the Rhine River and then across the Atlantic by the thousands. The flow increased even more when Queen Anne of Britain died childless in 1714, leaving the crown to her German cousin, George the Elector of Hanover. By the 1760s some 100,000 Germans had immigrated.

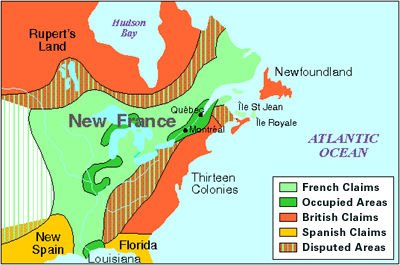

Thanks to its status of not giving two shits about such things, Pennsylvania was the most popular destination for most of the German immigrants, who made up more than a third of the colonies population by the 1760s. However, it was not the only destination. Groups of Germans also settled in Georgia and the French colony of Louisiana. As well, many Germans in Pennsylvania, finding little available land, moved south along the eastern foothills of the Appalachians, settling lands as far south as North Carolina. By the time of the American Revolution, nearly 10 percent of the population of the British colonies was German.

Though respected and viewed as being hardworking and industrious, many of the English-speaking descendants of the original colonists did not take kindly to the arrival of the Germans, beginning a trend in American history which continues through today. The already established colonists refused to let the Germans settle the more fertile lands near the coast. They also referred to the Germans as Dutch, because there were already Dutch around and they kind of sounded the same anyways so fuck it. For their part, the Germans seemed to have little interest in assimilating with the already existing customs. They instead formed tight knit communities where they retained German language, customs, and food. Though they were almost entirely all Protestant, most were Lutherans, which did not mesh well with the other Protestant faiths already established. As a result, a bit of a chicken and the egg situation arose, wherein the descendants of the English colonists disliked the Germans because they remained distinct and therefore foreign, which in turn gave the Germans the impetus to remain apart from the broader colonial society. This distinction did not begin to wane until well into the nineteenth century.