It’s probably worth mentioning at this point the very different worldviews which dominated the eastern half of North America during the first half of the eighteenth century. On one end of the spectrum was the British, who for a myriad of reasons you should have probably picked up on by now, largely viewed the New World as an empty void perfect ripe with opportunity for new beginnings. Whether that new beginning was dreams of a utopian society, free fertile land, or get rich schemes, it drew thousands of people across the Atlantic, both voluntarily and by force, who thanks to the relatively mild climate, created a level of prosperity which made popping out a ridiculous number of children make sense. As a result, the population of the British colonies quickly rose into the millions, while in comparison, the population of New France was only around 70,000 or so.

There are many reasons for this discrepancy, which can pretty much be boiled down to the kings of France were dicks and nobody wanted to move to New France. Now at the time, the French monarchy ruled with pretty much absolute dictatorial powers, both at home and abroad. While the British largely took a laissez-faire approach to their colonies, largely leaving them to run themselves as long as they were productive or at the very least not disruptive, New France was run with a more feudal flare, tightly controlled by appointed royal governors, who got to do whatever the hell they wanted as long as the king was cool with it. This combined with the fact that only Catholics were allowed to emigrate and that Canada was cold as balls compared to the mild French climate, created little incentive to cross the Atlantic permanently. As a result, most people who went only planned to do so temporarily, working a three-year contract in hopes of returning home if not wealthy, at the very least better off than they were before.

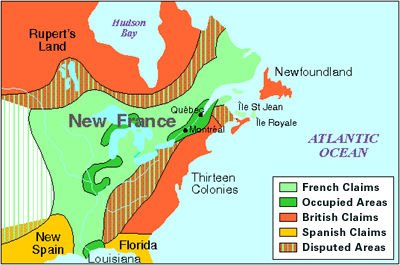

As one can imagine, this was somewhat concerning to those trying to make money off the colony, and though they did try several novel ways of increasing the population, such as shipping over desperately poor women who were either orphans or widows, it did little to help the problem. Due to this, New France remained largely dependent upon the relationships and alliances it built with various native tribes, exerting its power over wide swaths of territory via manipulation and trade centered on small forts often hundreds of miles from the next nearest French settlement. In affect the French were claiming territory over which it had little to no actual control outside of dominating trade, which was rather novel for the time. In comparison, though the British followed a similar model in some remote areas, as the populations of their colonies rapidly expanded they shifted more towards a just beat the shit out of anyone who didn’t get along with them mentality.

Now it should come as no surprise that overall the majority of native tribes largely preferred dealing with the French over the British, a mentality that only increased as the British population in North America continued to grow exponentially. These good relations allowed the French to wander much deeper into the continent, exploring and building a trading network across the whole of the Great Lakes and Mississippi watersheds, a network defended by various allied native tribes who increasingly became dependent upon French trade goods to survive. In essence, while the British colonists increasingly sought to control territory through domination, New France did it via symbiotic relationships.

Of course, there are always exceptions to the rule, the largest of course being the conflict between the French and the Iroquois Confederacy, which lasted for nearly a century and has already been covered extensively. There were also of course multiple proxy wars, wherein the French supplied arms to specific tribes in order to attack tribes allied with the British or tribes who were disrupting French trade in one way or another. Two of the most devastating of these took place in the early eighteenth century, when France was attempting to fully establish its trading network along the entirety of the Mississippi River. Meeting resistance from the Fox in what is today Wisconsin and the Natchez in what is today Mississippi, both of whom were traditional enemies of tribes allied to the French, the French and their allies fought a series of wars which ended in the near extermination of both groups, their members killed, enslaved, or scattered by 1735. The victories allowed the French to complete their trade network, which in turn allowed them to dominate the interior of the eastern half of North America, at least for a time.