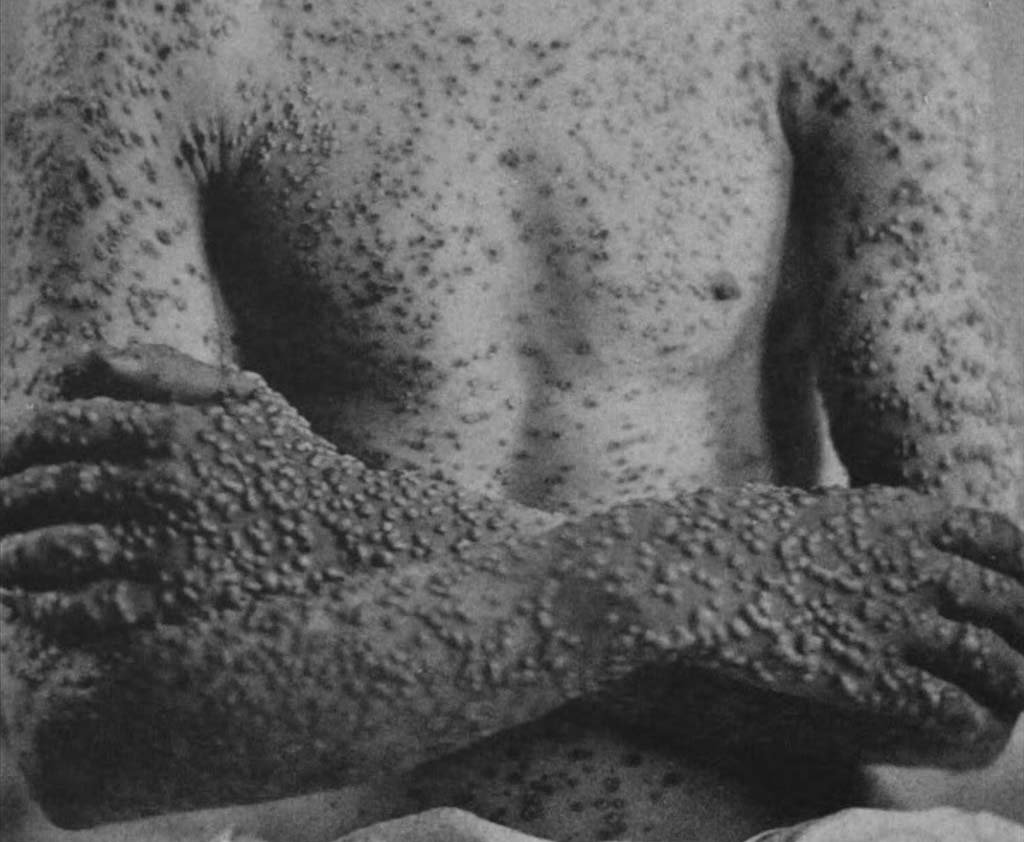

The American Revolution was a history changing event, but it wasn’t the only history changing event which began in Boston in 1775. While the Patriots besieged the British, smallpox began to spread, an outbreak which would grow into a continent wide pandemic. Of all the diseases faced by old timey people, smallpox was one of the most feared. It was highly infectious with symptoms not showing up for weeks, killed a high percentage of those who caught it, and left survivors forever scarred. So feared was the disease that by the time of the American Revolution all Thirteen Colonies had laws requiring newly arrived people off of ships be isolated for a period of time and laws requiring households be reported and quarantined if anyone in them showed signs of being sick, with guards often placed to ensure such measures were enforced. Basically people weren’t fucking around with it. Variolation was also beginning to become popular, a practice adapted from the Middle East where people put puss from a smallpox sore into an open wound to purposefully given themselves a more survivable low-grade infection, and therefore gain immunity. However, due to there still being a risk of death and nobody having a fucking clue how germs worked, it was rather controversial.

With volunteers coming from all over the place to fight, many periodically returning home, the pandemic quickly spread across the Thirteen Colonies and into Canada, wreaking havoc in an already very chaotic situation. Largely unaffected thanks to a policy of having all soldiers undergo variolation, the British army was more than happy to do little to nothing to stop the spread of the disease. The Continental Congress debated enacting a similar variolation policy for their soldiers, but debated over it for so long that George Washington just finally up and did it without permission, likely saving the war effort. The general population was not so lucky. With the breakdown in government authority efforts to halt the spread of smallpox was piecemeal and localized, resulting in it spreading far and wide and killing far more people than previous outbreaks.

From the Thirteen Colonies and Canada, the pandemic spread westward into the native nations of the Great Lakes, Midwest, and Southeast, following trade routes and marching Patriot and British troops. Though most of these nations had experienced outbreaks of smallpox many times by this point and had adopted practices such as quarantining anyone who showed any signs of being sick, the death toll was still as high a third of the population in some areas, further reducing their ability to resist future excursions into their territory by their colonial neighbors. By 1778, the pandemic reached the Mississippi and Missouri River basins where the death toll rose sharply. Less experienced with smallpox, the large Siouan and agrarian native towns were devastated, with the death toll as high as two-thirds of the population in some areas. At first less affected, the Sioux and other more horse-oriented nations seized greater control of the region, but quickly found themselves also falling ill. With numbers depleted, the various nomadic horse nations entered into a near constant state of conflict, raiding each other and the more agrarian nations not just for horses and European goods, but now also for women and children, intermingling cultures to a much higher degree than had previously been the case.

At the same time, the pandemic reached New Orleans and Texas in 1778 and Mexico in 1779, where it killed off a large percentage of the children in Mexico City before moving its way down through Central America and into South America. From Mexico, the pandemic also spread north, reaching the southwest by 1780, where it then spread to the Comanche, who spread it north to the Shoshone via their horse trading networks, who in turn spread it via their extensive trade networks across the Great Basin, California, and the Pacific Northwest, and finally into the furthest northern regions of the Canadian Prairies by 1782. Both the Comanche and Shoshone lost up to two-thirds of their populations, forcing them to lean more heavily into their reputations as formidable and vicious warriors to retain their territories, a strategy that worked for the Comanche but not as much for the Shoshone. Pushed southward by the Blackfoot Confederacy and westward by the Sioux and other Plains nations, the Shoshone lost power and prestige outside of the Great Basin. However, though victorious, the Blackfoot Confederacy soon after fell victim to the same smallpox malady which had laid their rivals so low.

The small pox pandemic of the late eighteenth century was the first time many native nations in the western half of the continent had experienced the devastating effects of Old World diseases. With little immunity, the results were devastating, spreading further chaos in a part of the world already in upheaval thanks to the introduction of horses and guns. Entire cultures shifted to survive in the new post-apocalyptic world in which they found themselves. Across the Plains and Great Basin large villages were abandoned, women and children became commodities, and a constant state of guerilla warfare became the norm.