In 1680, the Pueblo successfully revolted against the Spanish, who soon afterward left New Mexico, leaving behind thousands of horses. Recognizing a valuable commodity when they had one, the Pueblo traded the horses to the Utes, who in turn traded them to the Shoshone, effectively flooding the Great Basin horse market. The Shoshone, having already established that as a newly minted warrior culture they didn’t give two shits about anything, swept out of their ancestral homelands in the northern Great Basin and seized control over a vast swath of territory across Oregon, Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming, which they would hold for the next seventy years. The Shoshone in these early years proved to be an unstoppable force, taking on larger and formerly more powerful tribes and nations. Though unwilling to take slaves, they were more than willing to take captives, which they assimilated into their tribes to swell their numbers. By the end of the seventeenth century, they had developed a culture centered around the horse, fighting, and rapid mobility, annually migrating across their territories, hunting buffalo on the Great Plains, gathering roots and berries in the mountains, and hunting deer and other game in the desert.

By 1690, the Shoshone were so successful that a group of significant size split off from them in Wyoming, and began moving southward, hoping to become closer to primary source of horses in New Mexico. Moving into Colorado, they veered westward onto the Great Plains to avoid conflict with the Utes, where they became the first group of natives to completely transform themselves into a purely mounted nomadic culture completely centered on the hunting of buffalo. The Comanche, as they became to be called, first swept into the southern Plains of what is today Texas and Oklahoma in 1706. Over the next twenty-five years they completely displaced the Caddoan peoples and Apache who had formerly inhabited the area, pushing them northward and westward respectfully, controlling a vast swatch of territory known as the Comancheria by 1730. With the Spanish back in control of New Mexico, the Comanche began to both trade with them and raid deep into Mexico to secure more horses, which they in turn traded back north to the Shoshone. The success of the Comanche encouraged other groups to follow their example.

The Osage were a Siouan people who had been pushed westward by the Algonquian and Iroquois in the previous century. By 1690, they largely lived in Missouri where they farmed and hunted. Fueled by the great Puebloan horse glut, horses made their way across the southern Plains to the Osage who became early adopters, expanding westward onto the central Plains of what is today Kansas and Oklahoma to hunt buffalo. Gaining further horses and European goods, and eventually firearms, from trading furs with the French, they began fully transitioning to a buffalo-oriented lifestyle, pushing the Caddoan peoples already living in the area to the south and north, eventually becoming the dominant force on the central Plains by 1750.

In the north, after decades of unrivaled success, the horse rich Shoshone began trading the key to their success to their rivals. By 1730, the majority of tribes across the northern Plains and Canadian prairies had access to horses, and by1740 most of the tribes on the Columbia Plateau did as well. As a result, the Shoshone lost their advantage and began being pushed back by 1750. In the north, an Algonquian people known as the Blackfeet, thanks to horses and firearms obtained via trading furs with the Ojibwe, soon dominated large parts of Montana and the Canadian Prairies. On the northern Plains, numerous Algonquian, Siouan, and Caddoan tribes who had been pushed into the area shifted completely to a nomadic buffalo hunting way of life, trading and fighting with each other to secure prime hunting grounds and horses, which were scarcer on the northern Plains then in the south.

Over time a Siouan people known as the Sioux became one of the most powerful groups on the northern Plains. Inhabiting the western edge of the Great Lakes in the mid-sixteenth century, they increasingly came into conflict with the Cree who wished to remain the dominant trading partners of the French in the fur trade. Unable to defend themselves against the Cree, who had access to firearms, they moved westward into Minnesota and North Dakota, where gaining access to horses, they began to take on a more nomadic buffalo hunting lifestyle. For similar reasons as the Cree, the Ojibwe used their French traded firearms to push the Sioux further west in the 1760s, which completed the Sioux’s transition. This put the Sioux in direct competition with Siouan and Caddoan groups who lived in large well-established farming towns along the rivers, but after their populations were reduced by some 75 percent by a smallpox epidemic between 1772 and 1780, the Sioux quickly expanded, taking control of large swaths of territory and forcing other tribes already on the Plains to shift westward and southward.

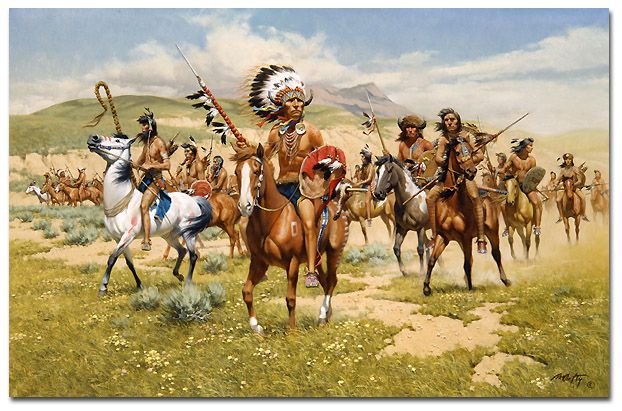

By 1770, the native horse culture of the Great Plains was mature and stretched from the Canadian Prairies in the north to the Rio Grande River to the south. Consisting of mounted buffalo hunting nomads living on the Great Plains and also including tribes from as far away as the Great Basin and Columbia Plateau who annually came eastward each summer. The vast horse herds required a significant amount of labor to maintain, resulting in men claiming multiple wives and taking captives in raids on rival tribes. Horses were not just prestige, but also the means of carrying goods, meaning the more horses someone had the more they could own. The number of horses someone had become a sign of wealth, and where once many of the tribes had been more egalitarian in nature, they shifted to more of a patriarchal and warrior culture. The large herds of horses began to degrade the grasslands, which in turn began to negatively affect a buffalo population which was already being negatively affected by overhunting. In the long run, it was an unsustainable situation, one which would only spiral further out of control with the arrival of Europeans in the next century.