Some twenty million years ago, when humans were just splitting away as their own type of ape, long before they even considered becoming the jackasses we are today, a new type of tree appeared in central Asia. The elm was a tall and stately deciduous tree, tough and resistant to most of what the world could throw at it. As a result, over the next many millennia, this bad ass of trees spread across central and eastern Asia, Europe, eastern North America, and even parts of the Indian sub-continent. Larger and taller than most other trees, with a distinctive shape, the elm quickly became sacred to many groups of people, often getting tied into myths surrounding death and the underworld. As humans progressed, they found more uses for elms beyond burning them to stay warm, such as bows to shoot arrows, chariots and wagons, boats, and even many of the first sewer pipes since it resisted rotting no longer how long it was wet.

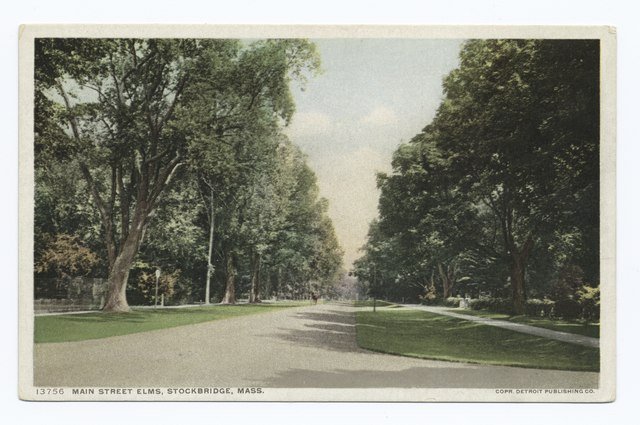

When European explorers began to spread out around the world, though they found many new and fascinating things, they also found many things similar to home. One of the more prominent of these were elm trees, though with some subtle differences, giants bursting with familiarity. Where these Europeans didn’t find elms, they planted them, giving themselves a taste of the old world. As people began to move from the countryside into cities, they brought their elm trees with them. Resistant to adverse climatic conditions and pollution, they quickly became the go to ornamental in cities and towns to the point that the majority of trees in parks and lining streets throughout Europe, North America, and Australia were elms. Avenues and boulevards arched by rows of towering elms became an archetype of the new urban world. That is, until Dutch Elm Disease hit the scene.

The first appearance of Dutch Elm Disease was in 1910 in the Netherlands, hence the name. Tree lovers, the science kind not the weird kind, began to notice leaves and branches dying on an increasing number of trees. At first it was only a few trees here and there, but by the time World War I came to a close it was being seen across the region, with many blaming the strange symptoms on poison gas used in the trenches. As can be surmised from the last sentence, at first people had no clue what was causing the problem, but eventually around 1921 some Dutch scientists figured out that the trees were being attacked by some kind of fungus that was being spread by bark beetles. I’m sure you’re very excited to learn all the details, so go read about them on your own. Anyways, over time the fungus spread rapidly, reaching the UK in 1927 and North America in 1928, carried over via imported lumber. Tree lovers, again the science type, began warning that if something wasn’t done, then millions of elm trees could die. However, before this could take place, the fungus mysteriously began to disappear, falling victim to various viruses. So ended, the dreaded Dutch Elm Disease.

Wait, no, that’s not right. I mean yeah, the part about Dutch Elm Disease becoming less common in the 1940’s is true, but not the part about it disappearing. No sirree, it just went into hiding, in Canada of course, where it secretly gave itself a makeover before springing back out into the world. In the mid-1960’s, it suddenly reappeared on the scene in much a more virulent form. Again hitching rides via lumber imports, it spread rapidly across its old stomping grounds, only this time taking no prisoners. Over the next forty years, millions of elms in Europe and North America died. Entire sub-species were completely wiped out. In North America, of the 77 million elm trees believed to be alive in 1930, less than 25 percent were still alive in 1990. Most of the UK and Europe became almost completely devoid of elms over the same period.

People of course didn’t just sit back and watch their elms die without a fight. Massive, at times national, campaigns began to save the elms. These early attempts mostly involved spraying gallons of insecticides over the trees, but this had little affect given the bark beetles that spread the fungus were small and the trees were very large. Next, prevention programs were initiated, where dead or dying branches were quickly cut away to try and save the rest of the tree. Many states and provinces also passed laws regarding when elm trees could be pruned and outlawing the use and sale of elm firewood. Fungicides have also become more popular, but with mixed results. Thanks to these efforts, the spread of the disease was at least slowed, but not stopped. Over the decades, millions of dollars have been spent on the problem.

Today, Dutch Elm Disease remains a threat to what few native elm trees still remain. Thanks to efforts by researchers, it is now understood that it first spread from Asia, where many of the local varieties have immunity. The disease was spread via the importation of lumber for making high end furniture. As a result of this research, many of these resistant varieties are now being interbred with European and American varieties to create new varieties that are being planted to replace what has been lost.

Image: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Main_Street_Elms,_Stockbridge,_Mass_(NYPL_b12647398-75756).tiff