Imagine yourself as a farmer on the Great Plains in 1874. It's the early summer and your fields are filled with your green crops waving gently in the wind. To the west, where you can just catch a glimpse of the distant Rocky Mountains, you notice what appears to be a great cloud of white vapor moving its way towards you. As it gets closer it becomes clearer. Trillions of individuals, sunlight flashing off their wings. Before you can even utter what the fuck they're on you. Trillions of hungry mouths. Where once stood your beautiful fields there is now nothing but bare dirt. They swarm over everything. Consuming, gnawing, and destroying. The trees are all stripped bare. You and your family try to save the vegetable garden by throwing blankets over it, but the mass just consumes both the blankets and vegetables. Then they start to eat the clothes off your back. Leather harnesses, the wool on sheep, pitchfork handles, and even paint. All is sucked into the millions of unquenchable maws. They start to pile up, more than a foot deep in some places. You and your family retreat into the house. They follow, battering themselves against the windows, crawling in through every nook and cranny. They're unstoppable. It lasts for days. When the skies finally clear you emerge to find the world of green transformed into grays and browns, the bare ground littered with their dead. Are you in hell? No, just a victim of the 1874 Rocky Mountain Locust Swarm.

A locust in reality is just a grasshopper. A grasshopper which, under the right conditions, multiplies by the millions, spreading across vast areas, destroying all in its path. Emerging periodically from the high mountain valleys of Montana and Wyoming, the Rocky Mountain Locust was once one of the most virulent of its breed. Throughout recorded history the swarms had periodically appeared across the Great Plains, usually every five to ten years. A series of wet years and mild winters would be followed by drought and the monsters would appear, blown eastward by the wind. Settlers first began coming to the Great Plains in the 1860’s. Under a government promise of free land, they emigrated en masse, cutting the vast grasslands with the plow. The locusts were nothing new. Swarms swept across various areas, but nothing compared to the monster that was unleashed in 1874, a force of nature the size of California which swept across the Great Plains like a battering ram of shit.

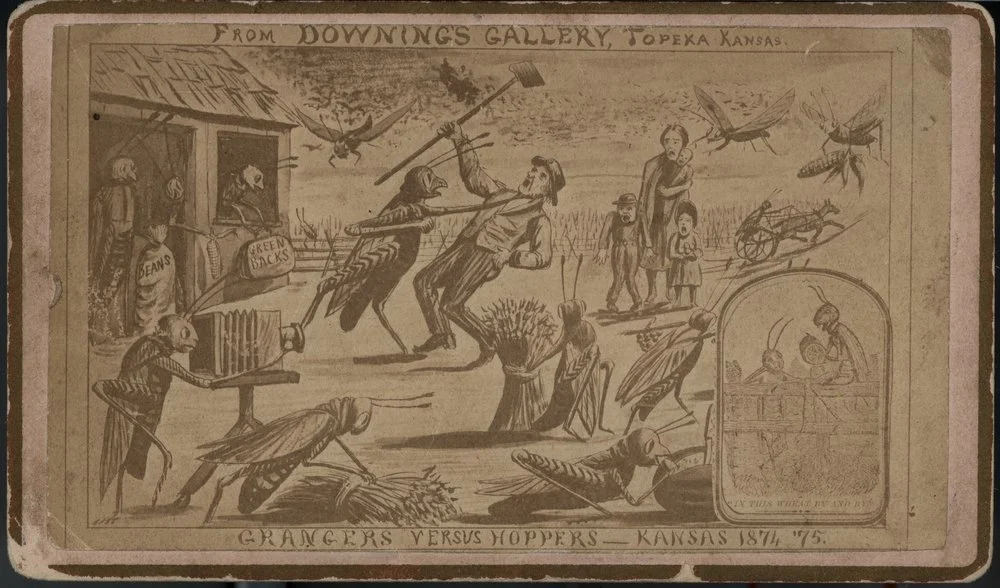

As the earliest reports of the devastation moved east, farmers in the swarm’s path began to gird themselves for battle. Their efforts were born of a mad desperation. Some of the more clever people rigged up vacuums or other devices to try and kill as many as possible. Others dug long trenches and started fires in hopes that the smoke would keep them at bay. Others just fired shotguns into the air or swung boards wildly about their heads. The vacuums clogged, the fires were smothered, and the rest made about as big of a dent as one would expect. By the fall, the locusts had crossed Montana, Wyoming, North Dakota, South Dakota, Minnesota, Colorado, Nebraska, Kansas, Iowa, Oklahoma, and Texas. Farmers were forced to pull up stakes or face starvation. The state of Kansas lost a third of its population. The U.S. Army was ordered in to help those who remained by delivering food and blankets. The livestock survived by eating dead locusts, though it made the animals sick and ruined their meat. Even some of the people ate the locusts, fried and stewed, sprinkled with pepper and salt. The locusts came again the next year, and the year after that. Eggs laid by the original swarm across the Great Plains hatched, releasing a terror that increasingly moved its way eastward each year.

Partial salvation from this terrible plague came from the Mennonites, a religious group that had been expelled from Russia for being a cult. With them they brought seeds from the wheat they had grown back home in Russia. At the time, most of the Great Plains were planted with corn and spring wheat, which is wheat planted in the spring and harvested in the fall. The Mennonites brought with them winter wheat, which is planted in the fall and harvested in the summer, before the locusts descended from the Rockies. Within only a few years the farmers of the Great Plains en masse switched to winter wheat.

Salvation also came from the state governments. Bounties were put on locusts killed during the spring time, before their numbers could become overwhelming, with payouts made by the bushel. By 1878, the last remnants of the Great Swarm of 1874 were gone. That same year, the U.S. government created a special branch to study the phenomenon. It proved unneeded. The Rocky Mountain Locust never appeared in such numbers again. Farmers moved up into the high valleys of Montana and Wyoming, farming the isolated sanctuary habitats where the swarms had their starts. A few small swarms appeared here and there, but by the start of the twentieth century the Rocky Mountain Locust was extinct.

Image: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Locust_Plague_of_1874#/media/File:Kansas_farmers_versus_grasshoppers_carte_de_visite_photograph.jpg