Prior to the foundation of the North American fur trade, Siberia was the dominant source of furs in the world. Traders from nations such as Russia, Sweden, the Ottoman Empire, and China had trading posts at the edge of the great frozen taiga from whence they traded good with the Siberian inhabitants for sable, fox, squirrel, and other furs. Not wishing to brave the harsh elements of the northern Asiatic interior, these nations otherwise left the region alone. However, this status quo began to end beginning in 1580. Over the prior hundred years, the nation of Russia had coalesced from the collapsing former Mongol kingdoms which had ruled the region, and the new nation was eager to prove it was a power to be reckoned with. By 1605, the last of the old Mongol kingdoms had been swept away, and the Russians set their eyes eastward, eager to dominate the ever more profitable fur trade.

Russia’s movement eastward into Siberia was part exploration and part conquest. Following rivers and establishing trading posts, the Russian heavily armed Russian expeditions forcefully convinced the locals to accept the rule of the Russian tsars, forcing them to pay an annual tax in furs for the right to live on lands their ancestor had inhabited for millennia. Though some resisted, victories in resisting were few and far between. Already sparsely populated, with likely no more than 300,000 people in the entire region, epidemics of smallpox and other diseases, introduced by the Russian expeditions, wiped out over half of the formerly isolated Siberian peoples. Those who remained largely lacked the modern weapons of the Russians and faced increasingly cruel treatment and torture if they resisted. The Russians reached the Pacific Ocean in 1639, and though scattered resistance continued for another century, they completely controlled the region by 1690.

At the start of the eighteenth century, Russia underwent a bit of a renaissance. A series of European educated tsars took a great interest in art, science, and literature. Not wishing to be seen as a backwards nation, they invested heavily in endeavors to prove Russia was the cultural equal of any nation in Europe. Amongst these investments were the funding of various scientific and exploratory expeditions, several of which had the mission of mapping out the eastward coastal extent of Siberia and Kamchatka, specifically to ascertain the possibility of a Northeastern Passage between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans and to see whether or not Kamchatka was connected to North America. The largest and most expensive of these expeditions, led by a Danish shit heel named Vitus Bering, became the first Europeans to step foot on what we today call Alaska in 1742.

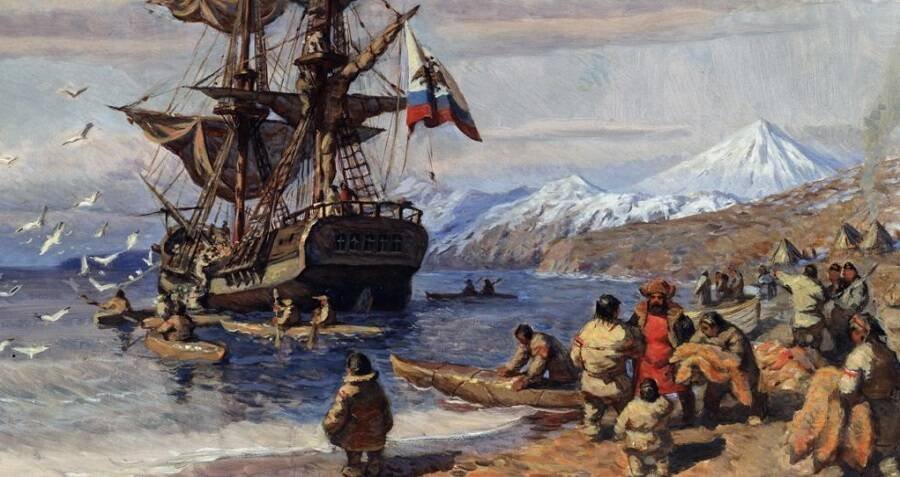

Now most people, Russian or otherwise, didn’t really give two fucks if a blank spot on a map was no longer quite as blank as it used to be. However, what they did care about was the abundance of sea otters in this new land, the furs of which fetched an amazingly high price in Europe and China. Not long after the return of Bering’s expedition, fur traders began crossing the ocean to Alaska to trade for furs with the local natives, the most prominent being the Aleuts of the Aleutian Islands. Now while many traders treated the Aleuts fairly, giving them European goods in exchange for furs, others went with the method of give me furs or I’ll fucking kill you. As one can imagine, this didn’t sit well with the Aleuts, who began resisting, but this resistance was short lived as they didn’t have guns, the Russians were vicious sons of bitches, and some 80 percent of the Aleuts died of various European diseases by the end of the century.

Though at first only using temporary trading posts, the Russians built their first permanent settlement, Unalaska, in the Aleutians in 1774. This was followed by the first permanent settlement in Alaska proper, on Kodiak Island to be precise, in 1784. Having heard of what happened with the Aleuts, this new settlement of course instantly came under attack by the local natives, to which the Russians responded by beating the ever living crap out of them, burning their villages, killing their children, and other various horrifying atrocities in the name of profit. Over time, these types of tactics, along with the accompanying wiping out of a significant part of the population via various diseases, calmed the situation somewhat, but not in a way that wasn’t shitty for the locals.